Practice makes perfect. My younger pupils actually quote this proverb back at me, because even in primary school they’ve understood the key point: if you cover a topic once but don’t revise it, it simply isn’t in your head any more — which means we did it for nothing and you have to start again from the beginning.

Let’s work out how to revise properly so that what you learn sticks for good; why missing a single lesson can cause a small catastrophe; and how to prevent that from happening. We’ll also learn how to avoid the traps set by our lazy brains and collect some useful resources that help you learn efficiently.

How Memory Works

Just like a computer, humans have working memory, which lets us process current tasks, and long-term memory, where we store absolutely everything that stays with us for a long time — from the colour of the shorts worn by our first nursery-school crush to the conjugation of Latin verbs we haven’t used for years but can still pull out as a secret weapon if needed.

Why do we remember the shorts? Because strong emotions help us remember. And the verbs? Because we learned them well: the teacher, together with a structured course and textbook, made us repeat them again and again — and they ended up in long-term memory. And this second way is easy to learn.

According to research, working memory can hold only four “chunks” (blocks) of information at once. In other words, its capacity is quite small, although it can be trained and expanded (for example, in interpreters, or in children who can multiply three-digit numbers in their heads in a couple of seconds).

Long-term memory, on the other hand, is limitless. Just think about that! It means that I — an ordinary person with no superpowers — can learn every language in the world, remember the names of every person on the planet, or memorise anything at all. In a healthy brain there’s no real “storage limit”; the only limits are lifespan, and the fact that we don’t need (or want) to remember absolutely everything.

The brain is made up of neurons — cells that form connections with each other, called neural connections. When we learn something new, the brain forms new neural connections. If we stop returning to that information, those connections stop being used and we forget it. Figuratively speaking, the thought stops travelling along that pathway of neural connections; the little track gets overgrown with weeds and thorns, and over time it becomes harder and harder to walk it again.

Similar processes happen throughout the body — for example, with muscles. Without regular exercise, muscles weaken because they’re expensive for the body to maintain. In the same way, neural connections that store unused information become weaker — which is why everyone keeps saying how important it is to study languages regularly.

Memory works like this: new information (not an annoying song on the radio, but something we consciously want to remember) requires revision. And not just revision, but revision at a certain interval after first encountering it, and then again at another interval — longer than the first. This has been studied and scientifically proven, and unless you have eidetic memory like Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory, this algorithm is for you.

Spaced Repetition

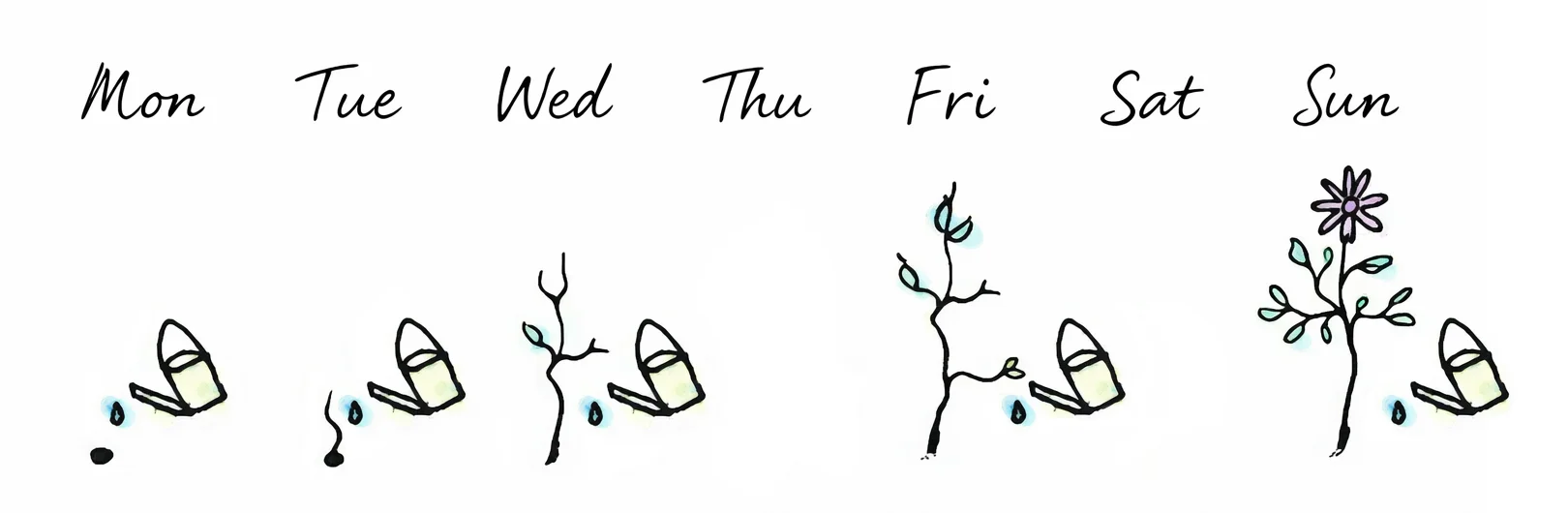

The Memrise app offers a great metaphor for forming neural connections. When we learn a new foreign word or phrase, we plant a seed in the ground. Each time we revise the word, we water the seed; it sprouts, the shoot grows, and eventually a big flower blooms. This isn’t just for looks: it’s designed to show how the spaced-repetition algorithm built into this and other apps forms the neural connections where words, phrases, and grammar patterns are stored.

After several revisions the flower blooms — meaning it’s time for the word to settle into long-term memory and for the neural connections that carry that information to become strong. If you then ignore the word for a long time and don’t revise it, the flower wilts and the app reminds you to water it — i.e. revise the word. The same thing happens to neural connections: if you don’t use them, they “wither”.

That’s why it’s so hard to return to a language after a long break: the neural connections have weakened and you have to train them again — which takes far more energy than maintaining them regularly, and it’s discouraging too: I used to be able to say this — and now I can’t. How is that possible? Still, if you built a strong foundation (foundations are my specialty), restoring a neglected language is incomparably easier than learning it from scratch.

So now we know how to use scientific findings for effective independent language study. Without getting into individual differences — your memory, your daily routine, and so on — spaced repetition theory suggests revising what you’ve learned at ever-increasing intervals.

For example: on Monday you cover a new topic in class. Ideally, you revise it on Tuesday and Wednesday, then on Friday, on Sunday, a week later, a month later, and so on — until you feel it’s going nowhere.

I’ve noticed that good textbooks present revision material in exactly this way, if you use them regularly (for example, the grammar textbook Foundations of the Italian Language by Greyzbard, which I’m very fond of). And of course, no one forbids you from revising a topic as many times as you need.

What’s the Best Way to Revise?

The first thought that comes to mind when you need to revise something is simply to reread the topic in the textbook. But you need to be very careful with this approach. When we look at a familiar text a second time, the brain doesn’t treat it as important new information — it just recognises it, like a familiar face, without taking anything in. It’s a trap!

The key is not to let your brain relax. You can and should reread the topic in the textbook — but while constantly testing yourself: immediately do an exercise on the topic that makes your brain work, or explain the topic to a classmate who will ask questions whenever something isn’t clear. Another option is to revise the same topic using a different textbook and different exercises.

I’ve had long breaks in language study myself. At first, when I tried to bring forgotten material back, I simply reread the rules and examples — but then I realised that although I recognised them and “remembered” them, I still didn’t start using the necessary words and rules in speech. Which meant the revision wasn’t effective. So I switched to other materials and started with exercises, working out the rules as I went and recalling the theory from practical examples — rather than the other way round.

For instance, an exercise contains the English word medium and asks you to make it plural. Right — there was a special rule. How do you form plurals of Latin-origin words? Ah, got it — I write it. In other words, I’m not rereading the plural rule point by point; instead I begin with the exercise and pick the relevant point for each example.

The second trap I’ve fallen into more than once is mechanical reading — or, as my grandad says when he sees me reading something, “Found all the familiar letters?” It’s true: I often catch myself thinking that I’ve read every word in a paragraph or even a whole page, and I know and understand them all — but I can’t reproduce the main idea.

When reading is disrupted by noise, someone else’s conversation, or intrusive thoughts, you sometimes reread the same bit five times and still get nowhere. And by the fifth time, your brain has started to treat the text as “native” and stops seeing it as something new — even though you still haven’t absorbed the information. Then you have to make an effort and read the text backwards (from the end) — that helps me.

Trap number three is revising the same material several times in one day. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work, because certain metabolic processes must happen in the brain for information to consolidate — and those processes occur only during sleep. In other words, revision within a single day counts as a single revision.

When is the best time to revise: morning, evening, or lunchtime? With our pace of life — whenever you can. It’s good to think about difficult tasks before sleep, because focused thinking gives way to diffuse thinking, which helps solve problems — and sometimes you wake up already knowing the answer.

With my own routine and body clock, I like revising and learning new material in the morning; then in the evening before sleep I revise the new material again; and the next morning I test myself — revision through exercises and tests.

You can find lots of practical knowledge about learning efficiently and “making friends” with your brain in Barbara Oakley’s book A Mind for Numbers and in her free Coursera course Learning How to Learn (with Terrence Sejnowski).

How to Build a Study Programme

When you study independently, it’s very important to account for revision time. For example, once I decided to learn yet another language, and in a burst of enthusiasm I planned to complete one grammar lesson per week.

One lesson in the textbook included about five grammar topics, fifty new words, and twenty pages of texts, rules and exercises. And it’s true: if I revised nothing at all, studying one hour a day I could have managed it. But only a “spherical horse in a vacuum” can do zero revision, so with revision the programme took twice as long — and I had to adjust it seriously. Yes, it’s disappointing, but we want a real working language, not a tick on the first page of a notebook.

So you need to allocate enough time for revision. How much exactly depends on how intensively you learn new material, the intervals between sessions, and the point at which your brain flatly refuses to absorb anything new.

For me, with languages, that happens after three hours of studying in one sitting; for some people it’s more, for others less. And I can’t do the same type of work for more than six hours a day. So after three hours the incoming stream shuts off, and in the remaining three hours I can only revise, do tests, or relax by watching a series. You can only learn this about yourself by trial and error — and then you’ll understand how to build a sensible programme.

Besides revision time, it’s useful to include materials that help you revise theory through practical exercises and tests, like in my example. For that purpose, I buy exercise books.

For beginners and intermediate learners of English there is Golitsynsky’s Grammar: A Collection of Exercises, and for Italian learners there is Tommaso Bueno’s Esercizi per la lingua parlata. The number of exercises offered for each topic in these books is excessive — and that’s wonderful: each time you revise a topic, you can do new exercises.

What Happens When You Skip Lessons?

Suppose an English course is designed for three months — either covering one level or preparing for an exam. Three months is a long time, and you can accomplish a lot. For example, classes are one hour once a week — so over the course you’ll have 12 lessons and 12 homework assignments. In each lesson you revise one old topic and learn one new one.

Now suppose you irresponsibly miss one lesson. It feels like it’s just one hour out of three months, right? But the brain does a different kind of arithmetic.

- You didn’t revise the previous lesson’s topic on time, so it will quickly evaporate from memory. You didn’t cover the new topic either. And the next lesson will have to begin with substantial revision.

- So it’s not one lesson, but already three lessons (a quarter of the entire course!) that will be inefficient.

- And if, for some reason, you also didn’t do the homework, then you missed not 1 but 2 to 4 effective “touches” of the language. And memory won’t forgive you for that.

Now imagine what was happening in our heads with all the information we were taught at school, especially towards the end of the academic year, over the summer holidays.

Everything covered in May was definitely not revised a month later — which means we won’t remember the new material studied in that month either, because it didn’t have time to settle into long-term memory.

The only useful thing about May is revising past topics and clarifying questions — but in the race to get through the syllabus, teachers often have to introduce at least some new topics at the end of the year, and as we’ve already understood, that’s pointless. And as far as I remember my school years, we didn’t manage to cover the whole syllabus in many subjects anyway. And that’s actually not a problem.

After everything we’ve learned, it’s clear why every time you start learning a foreign language and then quit, you end up having to start almost from scratch. Primary school children have already worked it out — which is why they keep studying even in summer.

What If You Really Have to Skip a Lesson?

This is what I did throughout my studies. You phone a classmate (ideally on the day of the lesson) and quiz them until you know, in detail, everything that happened in class. By the way, if your classmate has to explain a new topic from scratch, that’s useful for them too. Then you find out what homework was set and go and do it. At the next lesson, you обязательно ask the teacher questions about everything that still isn’t clear — provided you’ve already studied the topic on your own. You go through the homework in class. Result.

And Now a Revision Test!

What are the main ideas and tips about revision mentioned in this article? Write a short cheat sheet for your future use. Add your own tips as well.

And don’t forget to water your language garden! ;)

Resources to Help You Learn Effectively

- Barbara Oakley — A Mind for Numbers

- “10 rules of good and bad studying” from A Mind for Numbers

- Free course Learning How to Learn — about how the brain works, memory, procrastination, spaced repetition, attention and concentration, and aptitude for science and humanities.

Spaced-Repetition Apps

- Memrise

- Duolingo

Image Sources

- Students, photo by Alexis Brown on Unsplash

- Flower, author’s illustration

- Planner, photo by Sophie Ollis on Unsplash

- Desert, photo by Ivars Krutainis on Unsplash

- Tulips, photo by Victoria Heath on Unsplash

Research

- Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, M. C. (2009). Memory. NY: Psychology Press.

- Carpenter, S. K., Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24 (3), 369–378. doi: 10.1007/s10648-012-9205-z

- Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24 (1), 87–114.

- Djonlagic, I., Rosenfeld, A., Shohamy, D., Myers, C., Gluck, M., & Stickgold, R. (2009). Sleep enhances category learning. Learning & Memory, 16 (12), 751–755.

- Dudai, Y. (2004). The neurobiology of consolidation, or, how stable is the engram? Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 51–86.

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14 (1), 4–58.

- Durrant, S. J., Cairney, S. A., & Lewis, P. A. (2013). Overnight consolidation aids the transfer of statistical knowledge from the medial temporal lobe to the striatum. Cerebral Cortex, 23 (10), 2467–2478.

- Ellenbogen, J. M., Hu, P. T., Payne, J. D., Titone, D., & Walker, M. P. (2007). Human relational memory requires time and sleep. PNAS, 104 (18), 7723–7728.

- Guida, A., Gobet, F., Tardieu, H., & Nicolas, S. (2012). How chunks, long-term working memory and templates offer a cognitive explanation for neuroimaging data on expertise acquisition: A two-stage framework. Brain and Cognition, 79 (3), 221–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.01.010

- Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: How much is enough? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140 (3), 283.